REVIEW of

TIMOTHY MOWL

William Beckford: Composing for Mozart

JOHN MURRAY 1998

William Beckford’s first biographer, Cyrus Redding, is clearly the origin of many anecdotes and legends surrounding the author. Redding’s work (Memoirs of William Beckford of Fonthill, Author of ”Vathek,” published in 1859) has remained one of the most cited sources of biographical ”Beckfordiana.” It is a rushed work, reconstructed from memory after the original manuscript had been suppressed, and it suffers from longevity and dullness. Yet it remains a cornerstone of Beckford research, coming close to an official biography approved by its subject.

Anecdotes from Redding’s work may easily be discovered in practically all articles and books on Beckford since 1859. Some of them are quite amusing. Beckford’s alleged acquaintance with Mozart is perhaps the most often repeated of all. Did he or did he not inspire the young virtuoso to compose an air for one of his operas? Beckford, Redding wrote, took lessons from Mozart at an early age and "used to relate that the fine air of ”Non piu Andrai,” in the ”Marriage of Figaro,” was originally struck out as a theme, during one of his lessons, on which the pupil was to compose variations." [Redding, vol. II, p. 54]

Today we are fairly certain that this anecdote is false. Perhaps Beckford and Mozart met during the latter’s stay in England? Perhaps they played together on some occasion? True or false, the anecdote has survived unchallenged in many biographies.

Unfortunately, Redding’s work has been instrumental in defining the way in which Beckford’s biography has been written. We have come to expect a chapter on Beckford’s spoilt youth, describing his first stumbling experiments with literature, art and architecture and how his love of ‘all things oriental’ - spurred on by the mysterious and perhaps ominous influence of his drawing-master Alexander Cozens (1727-1786) - led him astray on a path of narcissistic homosexuality. The following chapters would expand on the psychological mechanisms behind Beckford’s love affair with the very young William Courtenay and describe the social ostracism that followed its disclosal. Beckford’s obsession with solitude and his self-imposed exile at Fonthill would be seen in this light also; a deliberately disdainful gesture, renouncing the very world that renounced him. Beckford’s grand tour would demand at least a chapter. One or two chapters would be devoted to the construction of Fonthill Abbey, and legends and myths surrounding the site would be explored. Beckford’s collections of books and paintings - praised by some, derided by others - would be described. The sale and ultimate collapse of Fonthill would merit perhaps half a chapter. Beckford’s final twenty years in Bath, and the building of Lansdown Tower, would occupy a small part of the narrative at the end.

Beckford’s literary achievements would most likely be another natural focus of the biographical narrative. The story of how Beckford composed the main outline of his famous oriental tale Vathek (1786) in three days, and how his collaborator Samuel Henley betrayed his trust and published the work anonymously and without Beckford’s consent, would be told. Other works by Beckford would probably attract little or no attention. His satirical works, Biographical Memoirs of Extraordinary Painters (1780), Modern Novel Writing (1796) and Azemia (1797), and his travel-writings, Dreams, Waking Thoughts and Incidents (1783), Italy; with Sketches of Spain and Portugal (1834) and Recollections of an Excursion to the Monasteries of Alcobaça and Batalha (1835), would receive only cursory attention in their own right.

It is hardly surprising. Beckford remains a minor author and a major biographical attraction. The myth of Beckford effectively overshadows his literary oeuvre.

Architectural historian Timothy Mowl’s biography is the latest in a long line of biographies on Beckford, and although it claims to present a new perspective it too conforms mainly to the traditional outline of Beckford biography. The subtitle boldly advertises the emblematic importance the author ascribes to the Mozart anecdote - ”Composing for Mozart.” Mowl uses this phrase as a poignant example of Beckford’s ”great revision” which he believes has foiled earlier attempts at fixing Beckford’s biography: "[...] with some ten years on his hands and always a secretary to take dictation, Beckford set about the great revision. His life, purged and perfected, was going to be his best gift to posterity, a poet’s life with none of that outdated nonsense of metre and rhyme." [p. 301]

In consequence Mowl throws a suspicious eye on practically everything Beckford wrote. What is true - what was ”purged and perfected”? Can we really trust any of the ‘autobiographical’ materials (i.e. diaries and letters) that Beckford left to posterity?

Mowl believes not. If Beckford’s life is to be described accurately the biographer must trust no sources at first sight; examine watermarks, inks and handwritings; detect copyists and copies; reconstruct events with an eye to Beckford’s ”confidence trick” [p. 301] and generally observe a healthy scepticism towards any colourful anecdote simply enhancing the Beckford mythology.

This is certainly a sound attitude to adopt, and one that Beckford research in general would do well to imitate. Yet Mowl’s strategy backfires. Not all of Beckford’s ‘juvenilia’ (as Mowl sometimes seems to suspect) was composed in old age. True, many of the letters survive in copies or in drafts only, but this isn’t unusual for any author of the time and does not necessarily indicate attempted forgery. There may well have been other reasons beside vanity that made Beckford keep letters and revise them well into his eighties. As Mowl correctly states, Beckford reinvented his life in his letters and in his diaries. But it wasn’t simply because he felt the urge to better the image of himself.

Mowl, however - in his role as biographer - occupies himself mainly with the question of biographical veracity when it comes to the texts, portraying Beckford as a talented ”experimental stylist and pasticheur” [p. 66] obsessed with his public self. In this light Vathek becomes ”a reflection, a fictional diary” [p. 116], even an ”autobiographical allegory” [p. 120]. The Long Story (published in 1930 as The Vision) becomes ”tedious adolescent nonsense in which Beckford was practising one of his many ‘voices’, a mode of aureate gushing prose” [p. 63].

He has little patience for the subtler nuances of Beckford’s writings. A thought-provoking discussion of Beckford’s portrayal of ”Cozens,” which Mowl correctly claims was reinvented by Beckford in his texts ”into an ideal companion and inspiration of his idyllic youth” [p. 53] is never followed through. Mowl could easily have added other mimetic elements to the equation as ”Fonthill” as well as ”William” served similar purposes within Beckford’s literary cosmos.

In fact Beckford staged an entire literary production centred on the pivotal figure of ”Beckford,” and made Fonthill the vortex of a literary legend. Other characters were allowed to perform on the same stage yet the ‘story’ rarely touched on matters outside the main figure’s field of perception. Beckford staged his ‘autobiography’ as a literary undertaking conforming to various rhetorical or fictional strategies. The diary, the letter, the novel and the poem; all genres reflected aesthetic choices first and private choices second.

Mowl on the other hand forces almost every text by Beckford to serve as biographical evidence. Vathek (as we have seen) is interpreted according to a long-standing critical tradition as a roman à clef, where fictional characters equal characters in real life. One of the Episodes (which were intended to expand Vathek) is used even more freely by Mowl, who claims that it represents Beckford’s attempt to purge himself of ”an adolescent fantasy of incestuous love for his half-sister” [p. 139].

While these interpretations are in full accord with Mowl’s psychoanalytical perspective they contribute only sparingly to our understanding of the literary qualities and mechanisms that make Beckford still readable. Such aspects are, unfortunately, more haphazardly and traditionally explored in Mowl’s work.

If one had expected this to be the biography to end all biographies on Beckford one is sadly mistaken. It is not. It is traditional in outline, speculative in detail and simply contains too many errors to be wholly satisfactory. An unfortunate lack of footnotes - what Mowl calls ”the tiresome but necessary impedimenta of scholarship” [p. 305] - effectively hides most of the shortcomings, and a general reader would no doubt find Mowl’s line of argument convincing and enjoyable. It is certainly well written. As an introduction to Beckford (and as the only major biography readily available) the book will therefore no doubt serve its purpose. It is advertised as a work of revisionist qualities, of which it has few. It should be read for the fluency of its narrative, for its emphasis on Beckford’s years in exile (the sections on Beckford in Switzerland are especially interesting) and for its portrayal of Beckford’s acquaintance with Disraeli and the consequences it may have brought about. But it simply fails to deliver where literature is concerned, thereby confirming - and in no way revising - the image of Beckford as a sloppy and self-indulgent writer, obsessed with his own reflection in whatever text he was writing.

It is certainly a pity. Beckford studies are in dire need of an authoritative biography that questions and disrupts those persistent biographical-psychological patterns which Cyrus Redding - and others - created.[This review will be published in ECN, vol. 1. Copyright Dick Claésson.]

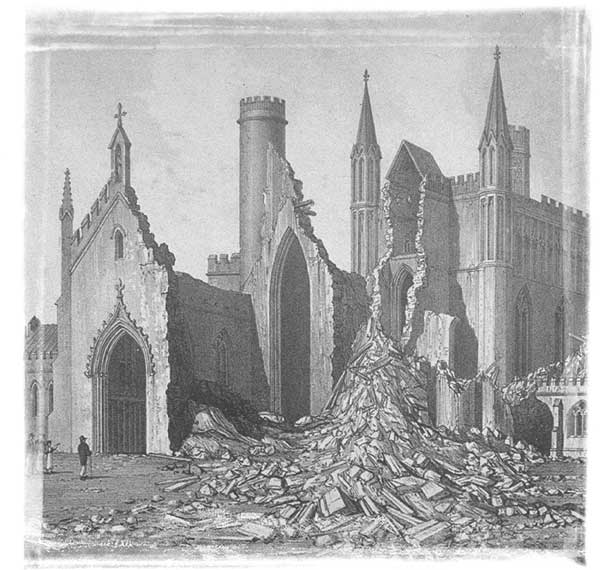

"Fonthill. – eheu! dilapsus Ao 1825".

Drawn by J. Buckler. Engraved by Thos Higham.(A detail)