Alfred Dunning:

"The Fantastic Builder"

Some Curious Characters

London & Glasgow [1948]

pp. 38-49

THE FANTASTIC BUILDER

Nowadays we hear a good deal about building and buildings. The need for new homes

- thousands of them - together with other buildings such as schools and hospitals,

is enormous. So it comes about that the planning and erection of such places

is a matter of first importance.

A building should, of course, be good to look at. But, at the present time especially,

its first qualification is that it should be useful. A new house, for instance,

must be handy to look after, and so designed that there is nothing in it or about

it which is inconvenient or foolish. Indeed, if an architect were to plan a house

or any other building which was not useful and practical, the authorities would

refuse to allow it to be built.

Now the tale that follows concerns a time when such regulations did not exist

and when, on the contrary, one of the most fantastic building schemes ever thought

of was carried out.

The "hero" - though that is hardly the right word for him - was a

man whose ideas on buildings and their planning were as extraordinary as the

size of his fortune. This was so vast that he could well afford to be foolishly

extravagant and-but it is time you learnt something more definite about him.

His name was William Beckford and he was born in the year 1760. His father, a

well-known [39] Londoner who had a great deal to do with the government of the

city, was the owner of several very large estates in the West Indies.

The produce from these brought him enormous profits every year and so, when at

last he died, he was able to bequeath to his son William a great fortune.

At the time he came into possession of it, William was no more than ten years

of age, and so he was taken into the care of the Earl of Chatham, who saw to

it that the boy was well educated and carefully brought up.

The result was that by the time he was a young man Beckford was accomplished,

well-travelled and an excellent writer and musician; indeed, as far as music

was concerned, he had been taught to play the piano by none other than Mozart

himself. Beckford had one very serious fault, however. He was far, far too impulsive,

and his great wealth did not help him to overcome this failing.

To think of a thing was, with William Beckford, to expect its being done straight

away. In some ways this is better than the opposite fault of constantly putting

off doing things until to-morrow. But in Beckford's case impulsiveness often

went to the most foolish extremes.

By the time Beckford was old enough to take charge of his own huge fortune, he

had already shown great promise by writing a fine book, still to be found occasionally

at a bookseller's, which had the title Vathek.

[40] But as soon as he came into possession of his inheritance he abandoned what

might easily have been a great literary career, and began to model his life on

the pattern of a rich country gentleman. He went to live on his late father's

estate, near the village of Fonthill in Wiltshire.

For a little while this life satisfied him, but in those days of his youth he

was a restless spirit, and before long - after sitting for a short period as

a Member of Parliament - he went abroad and lived in Portugal.

A few years on the Continent and he was back again at Fonthill, but this time

all ready for the most fantastic act of his whole career. By now he had added

a knowledge of architecture-that is to say, the designing of buildings - to his

accomplishments, but the architecture he had studied was chiefly that which was

concerned with the planning of churches. The result was that when he finally

decided to build himself a new home at Fonthill, he first pictured and then began

to superintend the erection of a building which was designed to be like a great

cathedral.

Fonthill Abbey was the name he gave it, and first of all, in order to keep out

curious sightseers during its construction, he had a great wall put up all round

the estate on which it was to stand. This wall alone must have cost a fortune,

for it was no less than seven miles long and twelve feet high, with guards standing

at its several gates!

But if the Great Wall of Fonthill was an architectural curiosity, it was nothing

by comparison [41] with the abbey, of which Beckford began to manage the building.

The highest part of the estate was chosen as the site for the great tower and,

once it was chosen, Beckford's impatience caused the work to be hurried forward

at what for those days was a very high speed. Gangs of men were brought to Fonthill

and employed on all kinds of work in connexion with the construction. Some were

doing the actual building, others the mixing of the cement or the shaping of

the timbers.

As the great tower gradually rose in height, Beckford called for more and more

men and equipment. At one time he required a considerable number more carts than

he possessed for the loading of materials. By offering wages higher than anyone

else he obtained practically every cart and carter in the district. The fact

that by his doing so, farming in the area came to a standstill, and the farmers

themselves suffered considerable loss and inconvenience, never worried him at

all.

On another occasion, having need of still more builders, Beckford obtained them

from as far away as Windsor, where they were at work on the Royal Chapel of St.

George. That task had to be left until Beckford was pleased to release them from

his service!

And so, by dint of reckless expenditure of money, the tower of Fonthill Abbey

rose higher and higher. Yet even then this impatient, reckless, over-wealthy

architect was not satisfied with the rate of progress.

[42] So the order went out "Non-stop work throughout the twenty-four hours

of every day!" Then it was that the local people began to be quite sure

that William Beckford was completely out of his mind. And they came to this opinion

not without good reason.

Every night and all night lights galore twinkled from the tower-the moving lights

of torches carried up the scaffolding by workmen and planted here and there,

while the men did their best to build reasonably well by their far from brilliant

illumination.

It was obvious to many of them, as well as to those onlookers who, by stealth,

managed to get over the encircling wall and secure a near view of the building

operations-it was obvious that this hasty and therefore shoddy workmanship would

sooner or later show its weakness.

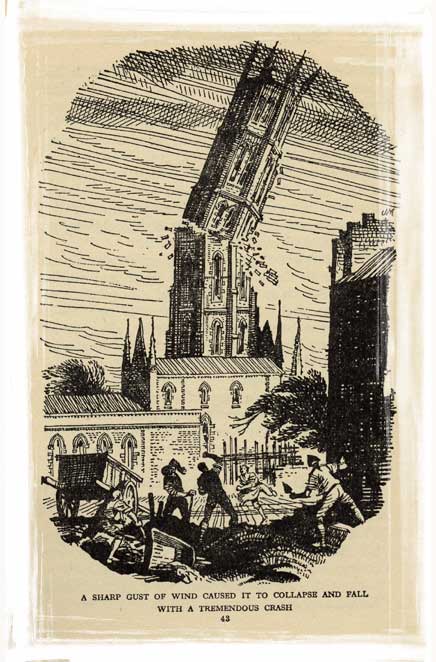

And so it did. One day, when the tower was all but finished, and luckily when

its three hundred feet of height had no one at work on it, a sharp gust of wind

caused it to collapse and fall with a tremendous crash. By the greatest of good

fortune no one was injured, and when William Beckford came on the scene his first

words were characteristic of him. "Build a new tower!" he ordered. "At

once!"

"At once!" Those two words would have been far better left out both

from Beckford's mind and from his orders. The old tower, which had collapsed,

had been built on very weak foundations, but when this was pointed out to Beckford,

the [43: illustration] [44] fatal words "At once!" came, uppermost in

his mind, and his impatience was such that he would not hear of the building

of better

and stronger foundations, but ordered the new tower to be erected, as was the

old one, on a most insecure base.

So again the work began, and this time the "pressure" if anything was

greater than the first time. Learning nothing from the first failure, Beckford

had a small army of well-paid men working night and day, by sunlight and torchlight,

to complete their work in record time.

Had this great speed of building been achieved in order to serve some really

great and useful purpose - such as the building of a hospital or of homes to

shelter a great number of people - it might have been most praiseworthy, although

as has been said, the quickest work in building as in anything else, is not necessarily

the most painstaking and thorough.

But when such a fury of energy was ordered merely to satisfy the vanity of a

man who wished to be different from everyone else, no matter what the cost, it

can only be regarded as wrong and wasteful - as later events show.

On 20th December, 1800, the tower was almost finished, thanks to the work, scamped

and slovenly though it was, of nearly five hundred workmen. That evening a distinguished

company left Fonthill House, not far away, and drove to the new abbey, as it

were, in state. Chief among this company, with their host Beckford, were Admiral

Lord Nelson and Sir William Hamilton.

[45] The route to the abbey lay through thickets illuminated by thousands of

coloured lanterns.

On arrival they found the abbey itself a veritable wonderland. There were rich

tapestries on the walls, purple curtains, candles in silver candlesticks, ebony

inlaid furniture and a repast laid out on a table fifty feet long, which made

the guests imagine they had been carried into some chapter of a story out of

The Arabian Nights.

To complete this strange and extravagant "house-warming" party, troops

from Beckford's "private army", engaged purely for decoration and not

for any form of battle, stood everywhere on guard, and a great fire of pine cones

heated the place and scented the air.

So far as history records, none of the many distinguished guests on that occasion

had anything but praise for Beckford's ingenuity and enterprise in providing

them with so remarkable a feast. And no doubt they would have thought it most

ungrateful had any one of their number questioned the intelligence of their eccentric

but open-handed host.

And yet had one of them lifted the rare tapestries and examined the walls they

hid, he might have found good reason to wonder whether, after all, it had been

wise coming to such a ceremony. For the walls, and indeed the whole structure

of the abbey, were in such an unfinished state that there was a very real danger

of the building collapsing on the heads of the guests gathered there to congratulate

its builder. The truth of this was shown [46] only a day or two later when the

morning of Christmas dawned. Beckford had given orders that the dinner for that

day was to be cooked in the abbey's kitchen.

The meal which had been served to his guests a few evenings before had been brought

from his other home, Fonthill House. But Christmas dinner, Beckford ordained,

should originate in the abbey kitchen-and Beckford's word was law!

The only trouble was that, on Christmas Eve, the building of the kitchen had

not been completed! Here again was a case for rush and hurry, and that kind of

work which nowadays we should call "Jerry building" - scamped, careless

construction which does not last.

Throughout the night the builders drove at it, so that Beckford's whim of having

Christmas dinner cooked there the next day might be satisfied. And when Christmas

morning arrived the kitchen was finished-but only after a fashion.

As you might expect, none of the bricks was set, for the mortar was not dry.

The beams and other woodwork, too, were merely "thrown" into position

and the place was, in short, far too "raw" to be used. Beckford, of

course, knew this well enough, but as we have seen, he was a man of great vanity,

and stubborn - perhaps stupid would be the better word-into the bargain. He had

ordered the cooking to take place there, and the cooking therefore would take

place there!

And the cooking did take place there! It was an excellent meal which the servants

laid before [47] Beckford and his guests in the dining-room of the abbey - and

it would have been perfect but for the great crash which interrupted the serving

of it. The crash was the collapse of the kitchen due to the heat of the fires

used in the cooking!

Not a part of the building which had been rushed up during the night remained

sound, but when Beckford was informed he showed no surprise and certainly not

the least trace of disappointment or worry. With a wave of his hand he ordered

the kitchen to be rebuilt and then turned to the meal - which in a sense had

cost hundreds of pounds to cook - and ate it with great relish!

There came a day when, though Fonthill Abbey was not completely finished, Beckford

left his nearby house and settled down in the new building to enjoy life as its

first tenant.

In many ways he lived like an emperor, or rather, as we might say in these days,

like a dictator. In spite of the great cost of building he still had an enormous

fortune which he would dispense with an open hand if ever the occasion arose.

A workman whose labour pleased Beckford might receive several pounds extra, over

and above his wages. He gave blankets and fuel to the poor of the surrounding

district as though he had unlimited quantities of both to dispense. On one occasion

he hired every cart in the area for the purpose of giving away coal.

But he was a creature of strange moods, and at [48] times, instead of giving

a poor man money he would suddenly turn upon him and thrash him with a whip.

When he did so, he almost always sent a servant to the person he had assaulted,

with a gift of money much greater than, he would have given in an ordinary case

of charity. And so, some of the less independent people in the district came

almost to welcome a flogging from Beckford of Fonthill!

After living at the abbey for several years in this fashion Beckford grew tired

of what was no longer a new toy, and bought a house in Bath.

Fonthill Abbey was therefore sold, together with most of its rich furnishings,

and its new owner paid Beckford the sum of three hundred and fifty thousand pounds,

which was even more than it had cost Beckford to build.

No wonder then he went away to Bath congratulating himself on a good stroke of

business, and a year or two later-and again about Christmas-time - he had occasion

to congratulate himself even more.

For in December of 1825 the tower of Fonthill collapsed in a heap of rubble!

Luckily the new owner was living in a part of the building farthest away from

the tower and so was not injured – indeed, neither he nor his servants,

who were in the kitchen, knew that the tower had fallen until country people

came rushing along to see whether anyone was hurt!

And so Beckford's fantastic project came to its inevitable end. As for Beckford

himself, he heard [49] of the collapse with no regrets. He was comfortably settled

in Bath where, with his wealth, he wanted nothing. And there he lived, apparently

without doing anything more of a fantastic nature, until his death at the age

of eighty-four.

I said at the beginning of this tale that the word "hero" was hardly

the right description for William Beckford. He did little which commands respect

or admiration. On the other hand, he was no worse than many another who is vain,

impulsive and a little thoughtless. Had he possessed less money he might have

done more good in the world: As it was he was like a child with a toy – only

his toy was an expensive one!

But, certainly, I think you will agree that William Beckford has more than a

right to figure in any book of curious characters!