W. P. Frith

My Autobiography and Reminiscences

London, 1887

vol. II, pp. 131-137

CHAPTER VII.

THE FONTHILL STORY.

THE

late Mr. Phillips, the well-known Bond Street auctioneer, was an intimate

friend of my uncle Scaife's, at whose

house I frequently

met him; and though I was a very young student fifty years ago, and quite

incapable of properly appreciating fine works of art, I often, at Mr.

Phillips's suggestion, visited his rooms whenever great collections were

dispersed

there. Hearing that a Holy Family by Raphael was to be sold, I

went to see it, and

though it was of doubtful authenticity, I thought it was a very fine

picture. I was discussing its merits – with all the ignorant assurance of youth – with

Mr. Phillips in his office, when an elderly gentleman walked briskly past

the door on his way to the gallery. He was a short man, dressed in a green

coat with brass buttons, leather breeches, and top-boots, and his hair was

powdered. "That is Mr. Beckford," said Phillips. I had just read "Vathek," and

was very curious to see the author of it; so I rushed upstairs to the auction-rooms,

and found the great little man studying the so-called Raphael. I [132] stood

close to the picture, and studied Mr. Beckford, who proceeded to criticise

the work in language of which my respectable pen can give my readers but

a faint idea. It must not be thought that the remarks were addressed to me

or to anybody but the speaker himself. "That d–––d

thing a Raphael! Great heavens! think of that now! Can there be such d–––d

fools as to believe that a Raphael! What a d–––d fool I

was to come here!" and without a glance at other pictures, the critic

departed.

It was many years after this that a distant connection of mine, who,

I must premise, was a person of an inquiring mind, found himself involved

in a curious adventure.

My relative had been in business, from which he retired at an unusually early

time of life, having acquired a handsome competence. He was married, but

childless,

and having bought a house in the salubrious city of Bath, he retired there,

and passed his time in reading and in finding out everything he could

about all the

people in the place. There was one house, and that the most interesting of

all, that shut its door against my inquisitive friend and everybody else.

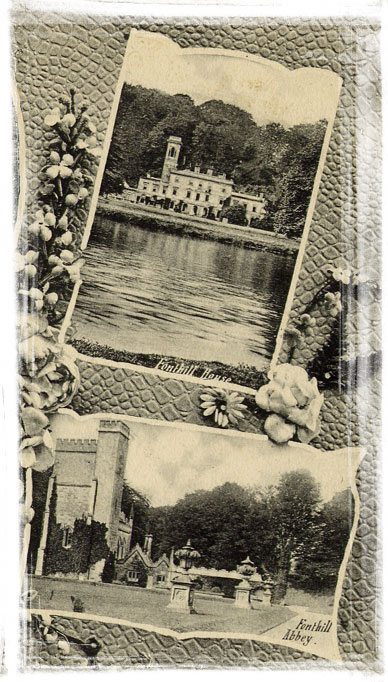

Fonthill

Abbey, or Fonthill Splendour, as it was sometimes called, situated a few

miles from Bath, was a treasure-house of beauty. Every picture was said

to be a gem,

and the gardens were unequalled by any in England, the whole being guarded

by a dragon in the form of Mr. Beckford. "Not only," says an authority, "had

the art-treasures of that princely place been sealed against the public, but

the [133] park itself – known by rumour as a beautiful spot had for several

years been inclosed by a most formidable wall, about seven miles in circuit,

twelve feet high, and crowned by a chevaux-de-frise." These formidable obstacles

my distant cousin undertook to surmount, and he laid a wager of a considerable

sum that he would walk in the gardens, and even penetrate into the house itself.

Having nothing better to do, he spent many an anxious hour in watching the

great gate in the wall, in the hope that by some inadvertence it might be

left open

and unguarded; and one day that happy moment arrived. The porter was ill,

and his wife opened the gate to a tradesman, who, after depositing his goods

at

the lodge (no butcher or baker was permitted to go to the Abbey itself),

retired, leaving the gate open, relying probably upon the woman's shutting

it. Quick

as

thought my relative passed the awful portals, and made his way across the

park. Guided by the high tower – called "Beckford's Folly" – my

inquisitive friend made his way to the gardens, and not being able immediately

to find the entrance, was leaning on a low wall that shut the gardens from the

park, and taking his fill of delight at the gorgeous display – the gardens

being in full beauty – when a man with a spud in his hand – perhaps

the head-gardener – approached, and asked the intruder how he came there,

and what he wanted.

"The fact is, I found the gate in the wall open, and having heard a great

deal about this beautiful place, I thought I should like to see it."

[134] "Ah!” said the gardener, "you would, would you? Well, you

can't see much where you are. Do you think you could manage to jump over the

wall? If you can, I will show you the gardens."

My cousin looked over the wall, and found such a palpable obstacle – in

the shape of a deep ditch – on the other side of it, that he wondered at

the proposal.

"Oh, I forgot the ditch! Well, go to the door; you will find it about a

couple of hundred yards to your right, and I will admit you."

In a very short time, to his great delight, my cousin found himself listening

to the learned names of rare plants, and inhaling the perfume of lovely flowers.

Then the fruit-gardens and hot-houses – "acres of them," as he

afterwards declared – were submitted to his inspection. After the beauties

of the gardens and grounds had been thoroughly explored, and the wager half won,

the inquisitive one's pleasure may be imagined when his guide said:

"Now, would you like to see the house and its contents? There are some rare

things in it – fine pictures and so on. Do you know anything, about pictures?"

"I think I do, and should, above all things, like to see those of which

I have heard so much but are you sure that you will not get yourself into a scrape

with Mr. Beckford? I've heard he is so very particular."

"Oh no!" said the gardener. "I don't think [135] Mr. Beckford

will mind what I do. You see, I have known him all my life, and he lets me do

pretty well as I like here."

"Then I shall only be too much obliged."

"Follow me, then," said the guide.

My distant cousin was really a man of considerable taste and culture, a great

lover of art, with some knowledge of the old masters and the different schools;

and he often surprised his guide, who, catalogue in hand, named the different

pictures and their authors, by his acute and often correct criticisms. So

intimate was his acquaintance with the styles of some of the different painters,

that

he was frequently able to anticipate his guide's information. When the pictures

had been thoroughly examined, there remained bric-à-brac of all kinds – costly

suits of armour, jewellery of all ages, bridal coffers beautifully painted by

Italian artists, numbers of ancient and modern musical instruments, with other

treasures, all to be carefully and delightedly examined, till, the day nearing

fast towards evening, the visitor prepared to depart, and was commencing a speech

of thanks in his best manner, when the gardener said, looking at his watch:

"Why, bless me, it's five o'clock! ain't you hungry? You must stop and have

some dinner."

"No, really, I couldn't think of taking such a liberty. I am sure Mr. Beckford

would be offended."

"No, he wouldn't. You must stop and dine with me; I am Mr. Beckford."

[136] My far-off cousin's state of mind may be imagined. He had won his wager,

and he was asked, actually asked, to dine with the man whose name was a terror

to the tourist, whose walks abroad were so rare that his personal appearance

was unknown to his neighbours. What a thing to relate to his circle at Bath!

How Mr. Beckford had been belied, to be sure! The dinner was magnificent,

served on massive plate -– the wines of the rarest vintage. Rarer still was Mr.

Beckford's conversation. He entertained his guest with stories of Italian travel,

with anecdotes of the great in whose society he had mixed, till he found the

shallowness of it; in short, with the outpouring of a mind of great power and

thorough cultivation. My cousin was well read enough to be able to appreciate

the conversation and contribute to it, and thus the evening passed delightfully

away. Candles were lighted, and host and guest talked till a fine Louis Quatorze

clock struck eleven. Mr. Beckford rose and left the room. The guest drew his

chair to the fire, and waited the return of his host. He thought he must have

dozed, for he started to find the room in semidarkness, and one of the solemn

powdered footmen putting out the lights.

"Where is Mr. Beckford?" said my cousin.

"Mr. Beckford has gone to bed," said the man, as he extinguished the

last candle.

The dining-room door was open, and there was a dim light in the hall.

"This is very strange," said my cousin; "I [137] expected Mr.

Beckford back again. I wished to thank him for his hospitality."

This was said as the guest followed the footman to the front-door. That functionary

opened it wide and said:

"Mr. Beckford ordered me to present his compliments to you, sir, and I am

to say that as you found your way into Fonthill Abbey without assistance, you

may find your way out again as best you can; and he hopes you will take care

to avoid the bloodhounds that are let loose in the gardens every night. I wish

you good-evening. No, thank you, sir; Mr. Beckford never allows vails."

My cousin climbed into the branches of the first tree that promised a safe

shelter from the dogs, and there waited for daylight; and it was not till

the sun showed

himself that he made his way, terror attending each step, through the gardens

into the park, and so to Bath. "The wager was won," said my relative; "but

not for fifty million times the amount would I again pass such a night as I did

at Fonthill Abbey."

I am in a position to assure my reader that this story of Fonthill Abbey

is absolutely true.